Wednesday, 29 October 2014

The Letter, A Story for Halloween

Saturday, 31 May 2014

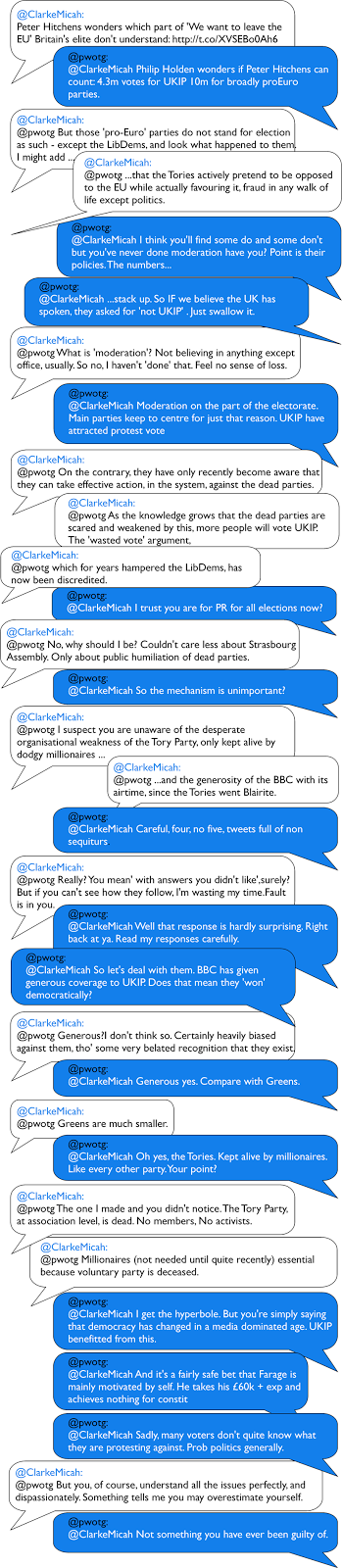

Fear and loathing in UK politics

Pondering, as you do when you argue and leave issues unresolved (let's give Hitchens the benefit of the doubt and accept that he was almost certainly too busy to reply, rather than crushed by my last tweet) I wondered why I felt so strongly about UKIP. What was the logical argument against celebrating their apparent victory in what can only be labelled a free and fair election?

Pondering, as you do when you argue and leave issues unresolved (let's give Hitchens the benefit of the doubt and accept that he was almost certainly too busy to reply, rather than crushed by my last tweet) I wondered why I felt so strongly about UKIP. What was the logical argument against celebrating their apparent victory in what can only be labelled a free and fair election?- Find out what worries people (fairly easy as we all have worries) something like health or our income.

- Make it specific. So not just health, but something like "If I fall ill, will I be looked after? Will I even get better?"

- Now take a (not necessarily a related) matter that you would like to promote. Oh, let's say...Europe. And, maybe add in another (again, not necessarily related fear or matter).

- Now nail them together in a statement that implies causation without explicitly linking them.

- And stir.

See my other blog at www.pleasewalkonthegrass.com and this especially on a Marketing Illusion.

Sunday, 16 February 2014

Pantomime

The President of the United States of America shifted in his seat. The lady he was watching was probably the same age as his wife, but she had one hell of a voice on her and, most of all, a hypnotic smile. What made him uncomfortable just now was that everyone around him clearly found her hilarious. He didn’t know why. Dammit. She was pretty hot.

She was tall and blonde, and her dress was extravagant. A cascade of purple sequins tumbled from her right shoulder, across her very significant chest and down to a frothy train that snaked behind her.

He always felt lonely on foreign visits. His wife was staying home for Christmas, whilst he had to be on another damn State visit, pretending to be nice to the British. They didn’t have anything he wanted and, thanks to the NSA, he already knew every bargaining chip they held.

Looking along the row of seats he could see the Prime Minister was beaming. Occasionally he would throw back his head and bark a laugh that could only have been developed at Eton. Or Oxford. Or wherever the hell prime ministers went to school these days.

Immediately behind the President sat his four bodyguards. And within the first four rows of theatre seats were various mediocre ministers and heads of tiny British Government departments. He should have sent his Secretary of State. But then he wouldn’t have met her.

He looked back toward the stage. The lady with the great smile was still singing and she was dancing too. A long leg with a glittering garter kicked from the slit in her dress. True, she wasn’t the most beautiful but, man, that smile!

An hour or so ago, when he had been introduced to her just before the show, she had seemed…what was the word? Irresistible. He stared at her smiling and working the room. Throughout the champagne reception she had been giving clear ‘signals’ in his direction.

She was dressed differently then; silver, shimmering like fish scales. It had been amazing. He had been introduced, but he hardly caught the name. Julienne? Something like that.

The President started in his seat, surprised by the sudden and enthusiastic applause that greeted the end of the song. The object of his fascination had curtseyed extravagantly and then began to announce something.

She was speaking English, he guessed, but the words were delivered in great swooping cadences and in an accent quite unlike the Prime Minister’s. The President just about made out that her character had a son called Jack who was evidently late back from doing something with a cow. It seemed to be causing the poor lady some distress, but still her smile sparkled mischievously.

No-one had seemed to notice when the President left the reception. It had only been for five or ten minutes. He had told his close security to go away with just enough expletives for them to take him seriously. Then he’d silently followed his new friend, the actress, into a small adjoining office where she had locked the door.

On stage, another character had now entered and was standing towards the back. Julienne pretended not to have seen the new actor, her soaring voice imploring the audience to do something. Something to do with Jack.

The audience responded and, for a moment, the President felt panic rise within.

“He’s behind you!” They screamed; their faces alight like the evangelical audiences he’d encountered in the Primaries. He looked along the row again. Yes, the Prime Minister was joining in. And his rat-faced Foreign Secretary. It was like the whole audience was possessed. Maybe there was something in the champagne? Then he noticed Jack and he knew something was wrong.

There was no doubt that in the play, this was the longed-for son Jack, because the lady with the scintillating smile was calling his name over and over…

“Ooooh! Jack, Jack, Jack, Jack, Jack!!”

She was clutching him to her substantial bosom and kissing his head. Again the audience found this hilarious. But the President was preoccupied. Was he the only one who had noticed?

Whatever else Jack was, he couldn’t be Julienne’s son, or anyone’s. Though not quite as voluptuous as the creature in purple sequins, ‘Jack’ had obvious, jutting breasts. His legs, clad in sheer tights and poured into long leather boots, went on forever.

The President shook his head, murmuring to himself. Weirdo British.

–

After the final curtain the VIPs were quickly led to the waiting queue of black limousines. It had been a strange day. On the plus side, the President had enjoyed the intimate attention of a beautiful stranger, and there were absolutely no witnesses.

As his car drew away, the glass partition in front of the President slid down and a figure in the passenger seat turned to him.

“Oh, Mr President.” It was the rat-like Foreign Secretary. “I hope you had an enjoyable evening.”

“What the hell …?” The President was irritated but stopped abruptly when he saw the envelope being offered to him.

“We thought you might like to see these. Before we get back to negotiations.” The rat smiled.

Frowning, the President lifted the flap of the envelope and slid out a handful of photographs. A series of stills taken from surveillance cameras. They showed two people in a small office, seen from above; one in a dinner jacket and another in a glittering ball gown.

As he flicked through them, his skin prickled. He took a moment to calculate. They couldn’t use these, could they? He looked up as coolly as he could.

“Well? I wouldn’t be the first President to get caught out. It’s a cheap trick.”

The rat didn’t flinch. The President continued.

“So, she was a honey trap was she? A sting?”

For a moment the Foreign Secretary looked puzzled and then a smile spread slowly and menacingly across his face.

“Her? Oh you mean Julian Barclay? One of our finest Shakespearean actors. You’re very fortunate to see him in Panto. You really should see his Lear.”

The President looked back down at the final picture in the sequence. The figure in the silver gown was kneeling in front of the man in the dinner jacket, refastening the Presidential flies. His face was turned towards the camera with a dazzling smile.

The President sank back in his seat.

“I think I just did.”

Written for the Tunbridge Wells Writers Group Advent Calendar from the keyword Pantomime